Why are there so few Welsh surnames?

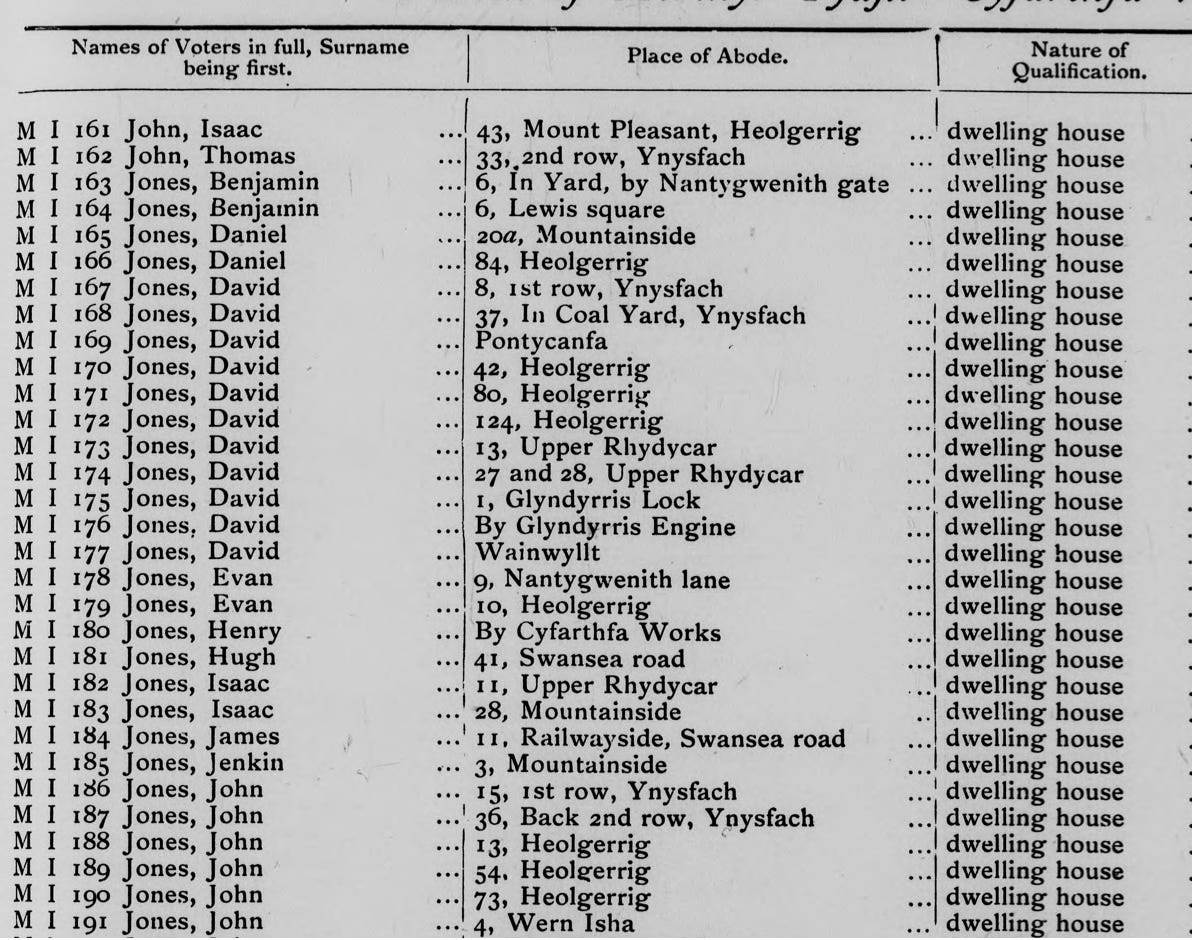

Unpicking Jones from Jones and Rees from Rees is a wretched task. But why do the Welsh have so few surnames?

Pity the family historian with Welsh ancestry. Unpicking Jones from Jones and Rees from Rees is a wretched task. Take my great-great-grandfather William Thomas. His census records say he was born in Swansea sometime between 1863 and 1866. Yet there were sixty-five babies called William Thomases born in Swansea in that time frame. I have a few theories about which might be him, but am not yet brave enough to make a definitive decree. But why do the Welsh have so few surnames?

It all goes back to the ancient patronymic naming system that was somewhat unique to Wales in the British Isles. Surprisingly the pains of modern genealogists can be traced back to a family historic fanatic. Hywel Dda (or Howell the Good) was the king of Deheubarth, who came to rule most of Wales in the 10th century. His major legacy is “the Laws of Hywel Dda”, which revised and codified traditional Welsh laws that had been passed down orally by jurists. One law dictated that a person’s family history should be widely known and recorded through the patronymic naming system.

Children took on the father’s given name as a surname, usually with a prefix of ‘ap’ or ‘ab’. This is a shortened version of ‘mab’, the Welsh word for son. Names could stretch at least nine generations back into the past, and might have looked a little like this: Dafydd ap Lewellyn ap Rhys ap Owen ap Gwasmeir ap Rhys ap John ap Gruffydd ap Meilyr. In the 1300s half of Welsh names looked like this and in some areas it could be much higher. It might seem rather convoluted but being able to trace descent from remote, tribal ancestors was actually a very good way of protecting rights to their land.

So why don’t Welsh people still use the patronymic naming system? Although the death of Lewellyn ap Gruffydd, the last Welsh Prince of Wales, during Edward I’s conquest in 1282, meant Wales had to adopt English-style counties and a new Welsh gentry who swore loyalty to England, it would take Henry VIII, an English king from a Welsh family, to wipe out Hywel Dda’s laws. Henry had a Welsh great-grandfather: Sir Owen Tudor, who was born Owain ap Maredudd ap Tudur in Anglesey around 1400.

But the Welsh might not have taken too kindly to Henry. He perceived that a threat was growing among remains of the old Welsh elite in the Marches and so instructed Thomas Cromwell, his chief minister, to seek a solution. The new policies were written up in the Laws in Wales Acts 1535 and 1542, which annexed Wales to the Kingdom of England, with the goal of creating a single state and legal jurisdiction.

The new laws meant that those English Lords who had been granted Welsh land by Edward I and their native Welsh contemporaries were made part of the English Peerage and that surnames became fixed amongst the Welsh gentry. The custom slowly spread amongst the rest of the Welsh people, although there is some evidence that the practice lasted until the early 19th century in some rural parts of the country.

But in taking on a fixed hereditary surname Welsh people felt that, perhaps due to the psychological legacy of Hywel’s laws, the most valuable part of their identity was not their job or their town, but their father’s name. This event when Christian names were also replacing pagan first names (like Llywarch) or Catholic devotional names (like Gwasmihangel). People across Europe were becoming quite frightened about what would be read into the names they gave to their children. So only around a dozen names became socially acceptable in Wales: John and Thomas being popular ones. So during the time when Welsh people were having to take on new hereditary surnames, but still wanting to honour their fathers, the result was that thousands of John Jones were born and tracing Welsh genealogy became a notoriously difficult process.