And I didn’t think this hobby could get anymore expensive. Last night I basically spent my entire weekend beer budget on 1921 census returns. But was it worth it?

For those that don’t know, the 1921 census was released last night by FindMyPast. In partnership with The National Archives, FindMyPast has digitised and transcribed more than 30,000 bound volumes of original documents that were stored on 1.6 linear kilometres of shelving and hold the records of 38 million people. Exciting stuff. For social historians this census will paint a portrait of a county still in mourning after the First World War. Expect to find many more single-parent houses: the number of widows rose sharply - from 642,311 in 1911 to more than 1.6m at the start of the 1920s. It was also the first census to allow people to say they were divorced. Only 16,000 people did so. This census also shows the depth of the 1920-21 economic depression, with many listing their employment as ‘out of work.’ One Yorkshireman sardonically wrote his employment status as being: “Out of Work in the Land Fit for Heroes.”

I actually found this census to be a little drier than previous ones. The aristocratic obsession with eugenics and the heath of the working class had faded, so unlike the 1911 census we do not get to find out whether our ancestors were “imbeciles” or “idiots.”

My worries that the census would be too close to living memory to tell genealogists anything particularly exciting about their forebears were also largely confirmed. I already knew the addresses they lived in and the exact number of people they lived with. Although I have seen lots of people say they have managed to break through brick walls in their research, I guess for most researchers this census will only really show their most intriguing and stubbornly secretive ancestors at the end of their lives. For example, my ‘Brick Wall Ancestor’ is on this census, aged 48 (she was 52) and says she was born in Dublin (she was born in Rawalpindi, now part of Pakistan). So rather than getting to break down a brick wall, I get more confirmation that she was a compulsive liar. I am not disappointed! It is just a shame censuses weren’t taken every five years rather than every ten, and I am sure others will be much more successful.

For that reason I am going to call the 1921 Census a specialist’s census. Because the gems that spring from it seem to be the really tiny sort that only the most obsessive genealogists will consider gold dust. Collector’s items, if you will. I didn’t know that my great-great-grandfather became the ‘store-keeper’ at his factory, for instance. Previous censuses said he was a ‘blacksmith’s striker’ or a ‘factory labourer.’ It may be why his blacksmith striking in-laws passed on an unfair family joke that he was lazy. Neither did I know that another great-grandfather had been a ‘store man’ for a flour merchant. All other records in his lifetime, including his death certificate ten years later, recorded him as a market gardener. It did remind me of a family story that he became bankrupt and had to close up. I don’t know whether he worked as a market gardener again, and this census record helps to bring colour to that moment in his life.

In fact, the employment tidbits on this census are what really makes it shine. Never before have we been able to see who our ancestors worked for and who they worked with. I knew from a 1920 marriage certificate that a great-grandfather in Swansea had been an ‘Erector’ but I had little idea of what this was (a scaffolder, perhaps, or maybe something more illicit?). The 1921 census informs me he worked for the ‘Motherwell Bridge Company.’ What were they building in Swansea? I can’t wait to find out.

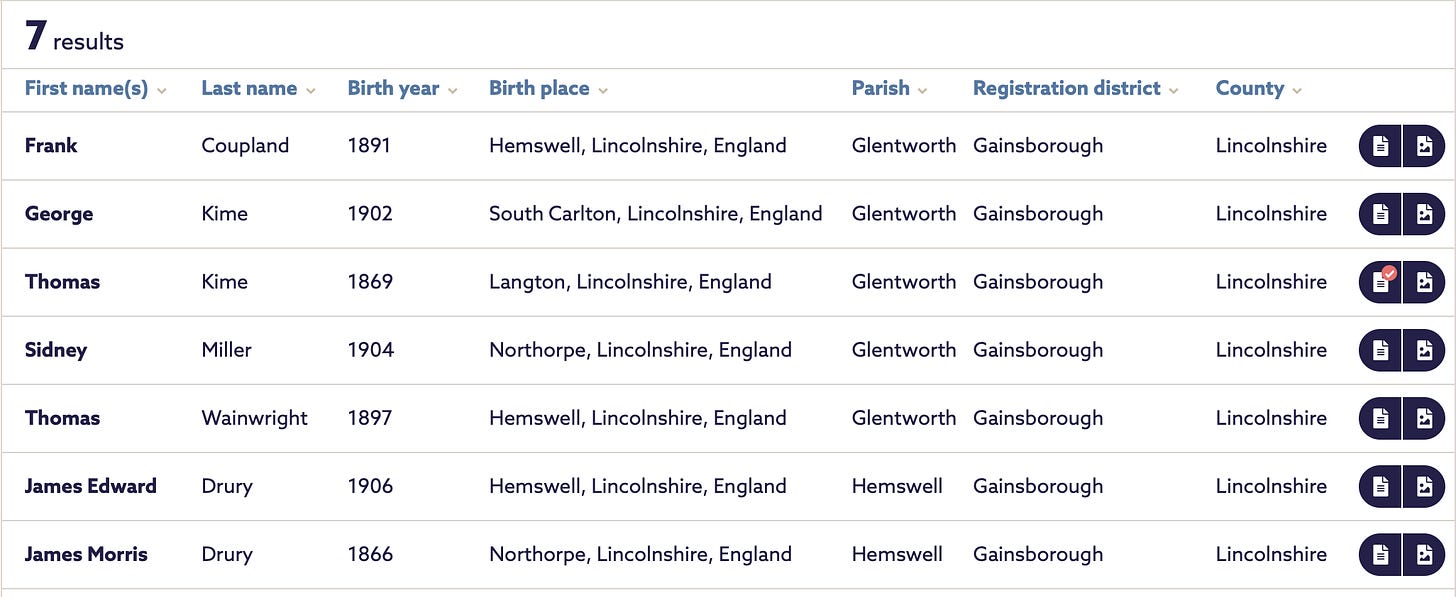

Here is where we get to the really special part of the 1921 census: the amount of effort that the transcribers at FindMyPast and the National Archives have put into bringing our ancestor’s work to life. This is why I would really recommend that people buy the transcribed records (£2.50) rather than the original records (£3.50). It has nothing to do with pricing but the lovely gobbets of extra information that the transcribers have worked hard to preserve. For instance, my great-great-granduncle Thomas Kime worked as a farm labourer. For the first time we can see who our many ‘Ag. Lab’ ancestor’s worked for and with. In 1921 Thomas Kime worked for a ‘C Tatam Farmer.’ The team at FindMyPast and the National Archives have then collected together everyone else who worked on that farm and allowed you to scroll through their names.

Imagine how useful this will be to genealogists with a grandparent born illegitimately in 1921-22, whose mother may have been a domestic servant and now they can see a list of people that may (or may not) be the father, one of whom might just match up with surnames found through DNA matches (see my previous post on illegitimacy).

Beyond that this very clever feature is a great tool for social historian genealogists who love to know how big a farm was, who the other employees were and what sort of daily gossip they would have discussed while at work. I just know that I will probably spend some time going through FindMyPast’s newspaper archives for these chaps.

So a specialist’s census it may be, but the 1921 census is certainly a great addition to the census family. Was it worth sacrificing my weekend beer allowance? Certainly.

Do you know the classic photo of a bunch of people sitting on a steel beam high above New York having their lunch break? They were erectors. Erectors were the field staff that went out to a site and actually erected the steel pieces (beams, posts, struts) into a structure. Despite the company name suggesting steel bridges, by the 20s most of those companies had diversified. Typical jobs were steel framed factory buildings, the steel frames for multistory buildings, transmission towers, and, of course, steel bridges. Such companies would work all over a very large region. You know that your grandfather had a fantastic head for heights.

Another excellent article and spot on. The transcribed record is full of little bits of information that can be useful if you are looking for the detail to confirm something you think you know. A lot of my research is based on oral history passed on to me by my mother. As everyone knows this is only as reliable as our collective memory and cannot be substantiated by the whys and wherefores which become lost in the past. My mother's memory of why her half sister was adopted by her mother's husband while she was abandoned is not entirely true. She only had half the story and seeing for the first time where the family was living in 1921 made me go ahhhhhh so that's what happened. It also confirmed what I had come to suspect about my grandma - always look out for number one. But then I have to put things into the perspective of 26 year old single mother (twice) with diabetes!