How common were first cousin marriages?

Many of us are descended from marriages between first cousins. How were these matches seen at the time?

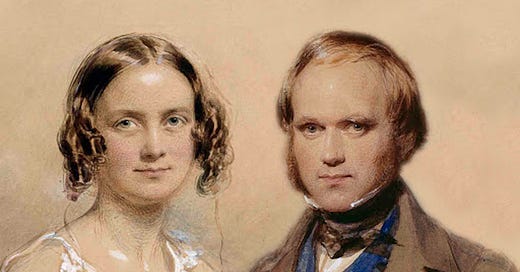

Charles Darwin had a special interest in cousin marriage. His wife, Emma Wedgwood, was his first cousin and their shared grandparents had been third cousins. Darwin was concerned that his children fell ill far too often and thought their inbred genes might be to blame. He set about studying the health of inbred animals and he experimented with self-fertilising different plant species. In 1868 he published his first conclusions (which he grandly termed “a great law of nature”): “the crossing of animals and plants which are not closely related to each other is highly beneficial or even necessary, and that interbreeding prolonged during many generations is highly injurious.”

Family historians often encounter cousin marriages in their research. There is a tendency to judge them with modern eyes as being odd or shameful affairs. I know of a genealogist who found out their grandparents had been first cousins and then never spoke about it again. There is another common tendency to believe inbreeding was so common and our ancestors were no awful degenerates. The truth is largely dependent on when the marriage occurred and the social class the couple belonged too.

In some ways modern attitudes to cousin marriage are the same as they were in the Middle Ages. Back then they were forbidden by canon law and influenced by biblical forebodings on taking spouses from your kin. Henry VIII, however, had other ideas. He legalised cousin marriages. Over the next few centuries cousin marriages became accepted practice. They had advantages, particularly for rich folk, as wealth and land was more likely to remain in the same gene pool if that gene pool was kept very small.

Scientists became concerned, however, that the offspring of cousin marriages were more likely to be “imbeciles.” In 1865, Arthur Mitchell, the Deputy Commissioner for Lunacy in Scotland, started to research the issue. There was a popular belief in Scotland at the time that ran contrary to that in most parts of England, which condemned “blood-alliances” as “productive of evil.” National statistics showed that 14% of Scottish “idiots” were children of kin. Such evil, it was believed, were to be found in the remote Scottish Highlands and Islands, where Mr Mitchell decided to do some more research. On Berneray-Lewis, in the Outer Hebrides, 11% of marriages were between cousins. But Mr Mitchell says he found no “island people with idiots, madmen, cripples, and mutes.” But he did meet an elderly woman who told him, with no hint of doubt, that hunger caused children to turn out “wrang” rather than incest. Mr Mitchell concluded that the truth was probably somewhere between the two.

Charles Darwin was fascinated by Mr Mitchell’s study, as was his inbred son George, a barrister and astronomer. George wanted to move beyond his father’s work on plants but could find no good data for cousin marriages in England. Estimates ranged from 10% of marriages to one in a thousand. He was not alone in finding a lack of trusted statistics frustrating. During the House of Commons debate on the Census Act, 1871, an attempt was made by John Lubbock, a noted polymath and the Liberal Member of Parliament for Maidstone, to insert a question about cousin marriages into the 1871 census. His plan was to compare the answers from the general population to those given by asylums, so to see whether the offspring of the latter was greater than the former. Unfortunately the proposals were met with scornful laughter in the Commons.

George Darwin set about finding the answers for himself. Using marriage records, press announcements and questionnaires, he found that some 4.5% of marriages among the aristocracy were between first cousins and 3.5% in the landed gentry. No wonder politicians found the matter so amusing. In the rural population it was 2.25% and in London it was about 1.15%. Proof, at last, that if the aristocracy lived in the same village it would be the most inbred village in England. He carried out similar tests in mental asylums and concluded that less than 4% were the children of cousins - not out of line with the rest of the population. He concluded that: “as far as insanity and idiocy go, no evil has been shown to accrue from consanguineous marriages.” His father was quite pleased. As were other members of his family. His cousin Francis Galton wrote to him that he should call his work “WORDS of Scientific COMFORT and ENCOURAGEMENT to COUSINS who are LOVERS” and make a tidy profit.

Oddly, though, George Darwin concluded that cousin marriages caused no harm in aristocratic families but that the poorest should be wary about the consequences. His findings proved popular among the House of Lords, many of whom had married their cousins. But an alternative movement had grown up in the United States. From the 1850s American scientists had found opposing evidence to Darwin’s happy findings. Many states banned first cousin marriages. Reports of people who were jailed in the US were printed in British papers. An example in the Dundee Evening Post in 1903:

After the First World Wr the public mood in Britain shifted against cousin marriages. There is little certainty as to why this happened and it is strange considering that the Darwins had done much work to dispel rumours of bad health among the offspring of cousin marriages. Perhaps it is because so many men died at war. Perhaps because people became much more mobile. Whatever the reason the numbers of incestuous marriages declined. By the 1930s, only one marriage in 6,000 was with a first cousin.

In 1920 the Dundee Evening Telegraph reported that Dr W. Bateson, a biologist, said: “I would sooner marry my cousin if I knew her family than marry someone else’s cousin about whom I knew nothing.” That attitude seems to have remained common among the aristocracy, as newspaper reports show the gentry still marrying their kin. But among people of Dr Bateson’s own class the practice was also declining. A study of middle-class Londoners in the 1960s found that just one marriage in 25,000 was between first cousins. Even as the practice has declined, scientists still remain split.

Understanding the history of cousin marriages can help family historians understand a little more about our ancestors who happened to be married to their cousins. The genealogist, who was embarrassed to find out their grandparents had been first cousins, probably had a right to be shocked. The grandparents had married in 1921 and had lived long enough to see the genealogist reach adulthood. Looking at the history of cousin marriages shows that social attitudes towards such unions had started to become fraught with disapproval. But when a relative of mine married his first cousin in 1878 very few people would have cared. And if you have noble or Hebridean ancestors, you might find a lot more cousin marriages than you’d expected.